Nelly Dyserinck

In this series about colourful figures in modern art and cultural life, we provide insight into a portrait or artwork from the RKD collection. This episode is about Nelly Dyserinck, a well-to-do lady who moved in the chique cultural society circles of The Hague at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Double portrait on a visiting card

This double portrait of Nelly Dyserinck with an unknown woman is part of an extensive collection of cartes de visite which are looked after by the RKD. Visiting cards such as this were especially a feature of life in the nineteenth century. It was generally a small portrait photo which was stuck onto stiff card. They were enthusiastically collected in particular by well-to-do women, who kept them in specially designed albums. The phenomenon of visiting cards quickly disappeared as new ways of making photographs became popular after the First World War.

Nelly Dyserinck is portrayed sitting and holding a book. Beside her stands a woman who has so far remained unidentified. As was very much the fashion of the period (the photo dates from c. 1880-1890), the women look serious and remote. Nelly was born in Haarlem into a distinguished family and she had three sisters, two of whom died young. Only her sister Annette, who was five years older, lived like her to a good age. Possibly she is the woman seen standing on this visiting card. The photographer Fritz Meycke, whose name appears underneath the photo, worked in Germany, from where Annette’s husband came.

Unexpected world

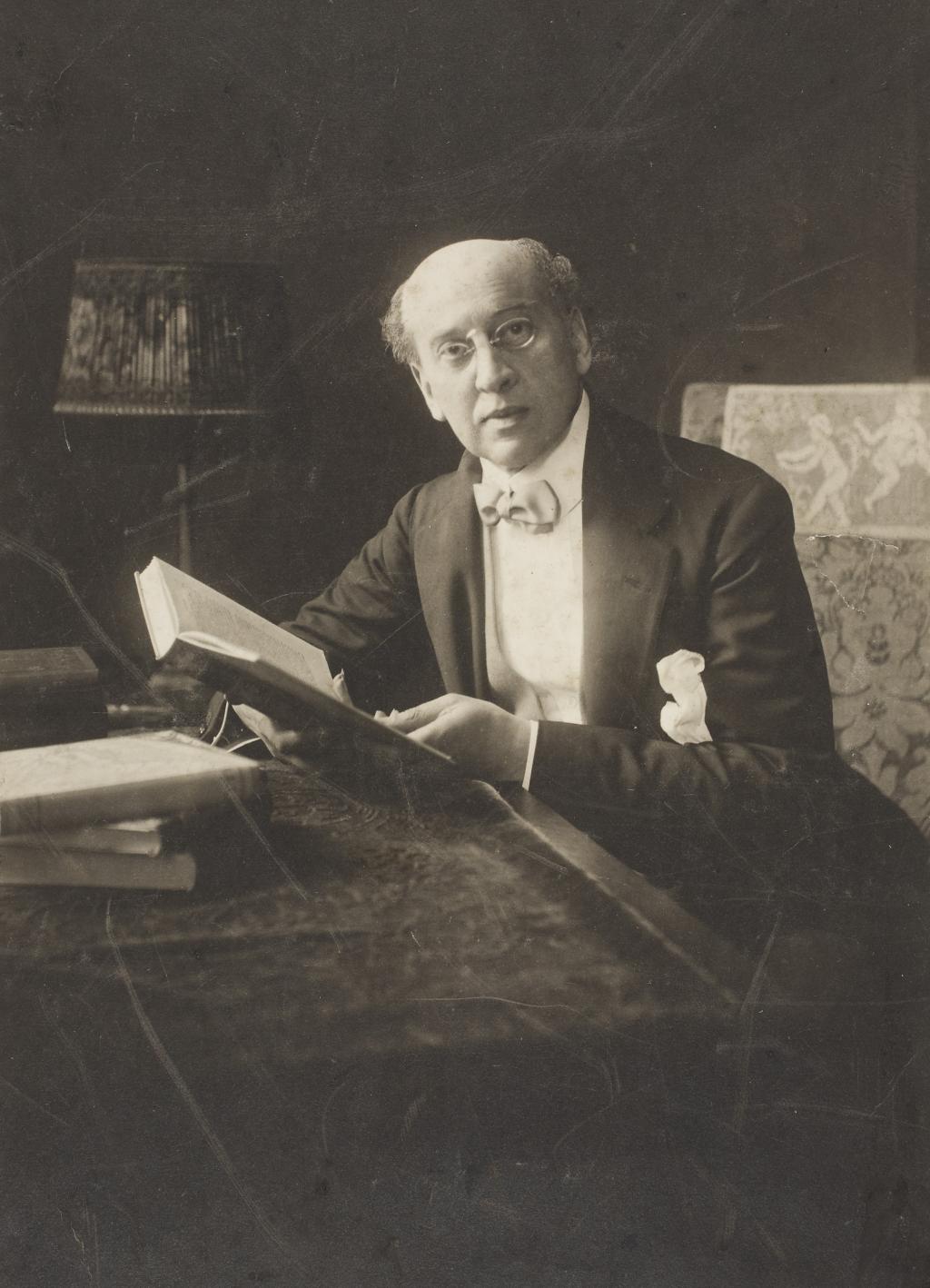

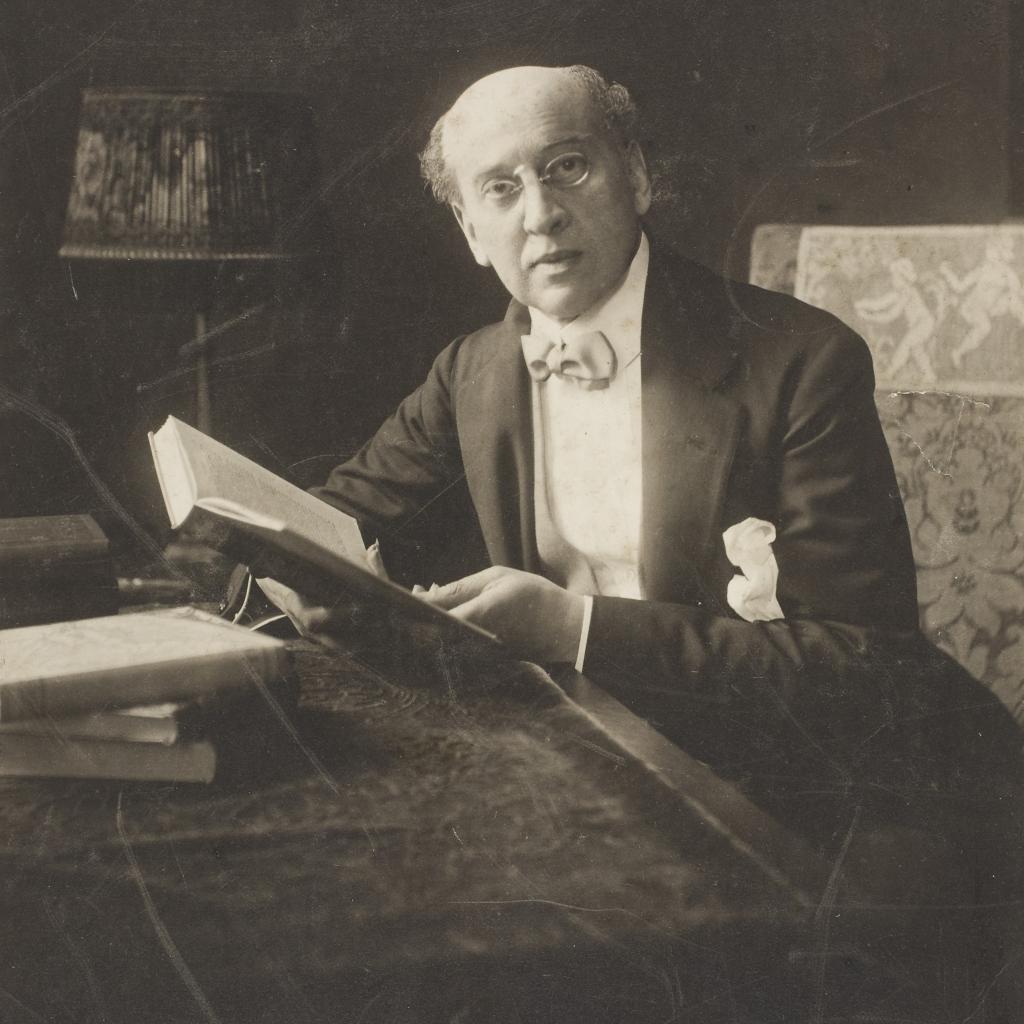

Behind this apparently ordinary portrait of two women lies an unexpected world. Nelly Dyserinck came to attention mainly through her two marriages to eminent men. She became well-known especially as the wife of the Flemish writer Cyriel Buysse (1859-1932), whom she married in 1896, after which for many years they lived in The Hague on the Laan van Meerdervoort. According to those who knew them, the couple maintained a sort of long-distance relationship, each following their own interests, but regularly spending the winter months in the city. In the summer months they liked to be in the Roze Huis in the Flemish village of Afsnee, near Ghent.

In the chique society of The Hague, the Buysse-Dyserinck couple were soon on good terms with the ubiquitous novelist and dandy Louis Couperus and his wife Elisabeth Couperus-Baud. This emerges from warmly written letters that Couperus sent to the couple, but addressed to Nelly, around 1900. Through her first marriage to Theodoor Tromp, who was the son of a minister and a committee member of the Haagse Kunstkring (The Hague Art Circle), Nelly was an insider in the literary life of The Hague. After returning from a civil service career in South Africa, Tromp became known as a writer. He published articles in magazines and newspapers, and wrote a number of novels, often situated in Africa. Tromp died at young age of an illness.

The Fleming Cyriel Buysse

Nelly’s second husband struggled to get used to the cool, solemn airs of The Hague’s fine fleur, as they were immortalised in Couperus’s books. As a true Fleming he missed the hearty plain speaking and liveliness of the area that he came from. He was an outdoor man and felt little at home in the city, whether in The Hague or Ghent. As the product of the upper-middle classes in Haarlem, his wife apparently found it easier to thrive in the regulated life of the Hague.

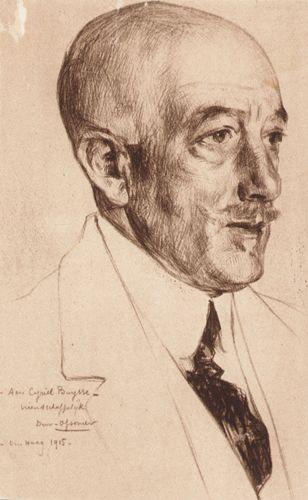

Yet, Cyriel Buysse became involved in many cultural activities in The Hague. For example, he was one of the founders of the literary journal Groot Nederland, which appeared from 1903 to 1944. During the First World War he wrote various sketches and stories about the war in his own country. He had a close relationship with the artist Isidoor Opsomer, who settled as an exile in The Hague in 1915, and who captured Buysse in a striking portrait. Another of the regular visitors to the Buysse couple’s house was the celebrated collector and art historian Cornelis Hofstede de Groot, one of the RKD’s founders in 1932.

Silent witness

Cyriel Buysse died in 1932 after an eventful literary career. Ironically this was four days after he was raised to the aristocracy as a baron by the Belgian king. Exceptionally, two years later Nelly was herself made a member of the Belgian nobility with the title of baroness. The title passed to the only son from their marriage, René Cyriel Buysse (1897-1969). In truth, Nelly Dyserinck’s fate was the same as that of many of her sex and generation, many of whom are remembered as ‘wife of…’. Much more is known about the biography of her two husbands than about her life. The visiting card from the RKD collection is a silent witness of her character.